During Sunday’s Chicago Triathlon, I kept my heart rate low, cut my pace at every hint of muscular or cardiovascular pain and crossed the finish line about half an hour behind my personal record in that race. It was exhilarating.

What I accomplished is a goal I once considered unreachable, not to mention undesirable: I raced without competing. My ranking among the more than 4,200 participants in the Olympic-distance triathlon couldn’t have mattered less to me. More important, I ditched the notion of competing against oneself. That had been an appealing concept at age 40, when I was fitter, faster and trimmer than I’d been at age 20. But at 50, the triumphs of the last decade—the time I flew past most of the few-and-proud at the Marine Corps Triathlon—are far behind me, and anyway my cardiologist is urging moderation since the discovery of an aneurysm in my aortic root. “Race all you want,” he says, “but keep your heart rate below 120,” far lower than most peak workout targets.

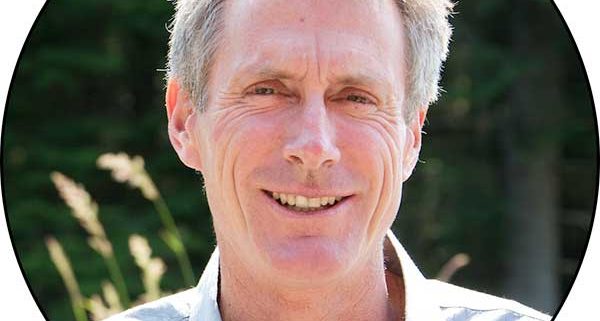

“If you have to go as fast at 50 as you did at 20, you will grind yourself into the ground,” says Mark Allen, a former triathlon champ once known as the world’s fittest man.

Amid ever-rising calls for more exercise in America, there isn’t much guidance on cutting back. As the baby boomers who fueled marathon and triathlon crazes enter their 50s and 60s, their unquenched competitiveness can become a threat to their stiffening joints, rigid muscles, hardening arteries and high-mileage hearts. And it doesn’t help that nearly every exercise message they hear emphasizes more. It’s as if nobody wants to acknowledge that exercise isn’t the fountain of youth.

“The no-pain-no-gain mentality suggests that you can keep making gains if you just work harder,” says Mark Allen, a 51-year-old athletic coach once known as the world’s fittest man for winning six Ironman Triathlon World Championships. As co-author of a new book called “Fit Soul, Fit Body,” Mr. Allen argues against fighting age with more hours on the treadmill. “If you can’t let up on the competitive part of it, if you have to go as fast at 50 as you did at 20, you will grind yourself into the ground and become stressed out, bitter and unhealthy,” he says.

A growing number of exercise scientists are questioning the more-and-harder philosophy of fitness, and not only for aging athletes. A study published last year in the Annals of Behavioral Medicine reinforced other recent research showing that intensity tends to diminish the view of physical activity as pleasant. “Evidence shows that feeling worse during exercise translates to doing less exercise in the future,” says Panteleimon Ekkekakis, an author of that study and a professor of kinesiology at Iowa State University.

Taking on new sports or challenges can give long-used muscles a break while feeding the desire for new goals, says Marjorie Albohm, president of the National Athletic Trainers’ Association, who at 58 has become a recent devotee of spinning. “As you age, you have to be flexible about new activities.

Of course, exercise can provide substantial protection against chronic ailments ranging from heart disease and diabetes to dementia and depression, all the while helping weight control. But like any medical treatment, exercise can also cause damage, particularly in older athletes. The risk of sudden cardiac death rises substantially during exercise. Overuse injuries, especially involving joints, rise with age.

Older athletes struggling against declining performance are prone to excess training, which can hurt the immune system and raise levels of the stress hormone, cortisol. A number of medical experts, including Kenneth Cooper, the physician long ago credited with founding the aerobics movement, now believe that extreme exercise can increase the body’s vulnerability to disease like cancer.

For aging athletes, it is loss of prowess that can lead either to abandoning exercise or to a health-endangering doubling up of it, “in pursuit of what can’t be recaptured,” as Mr. Allen puts it.

In his mid-40s, after dozens of triathlons and swimming competitions, Dan Projansky was yearning for something new, so he took up the unusual challenge of open-water distance swimming, using only the butterfly. That’s a stroke that wears out many accomplished swimmers after a few hundred yards. But this month, Mr. Projansky gained glory in national swimming circles for completing an open-water 10-kilometer swim using only the butterfly. “I belong in the psych ward,” jokes Mr. Projansky, a suburban Chicago insurance professional who is 51.

The competitive flame is hard to extinguish, as the returns from retirement of cyclist Lance Armstrong and professional quarterback Brett Favre have shown. And it’s no different for fanatical amateurs. A decade ago, marriage and children brought to an end the elite triathlon career of Matt Rhodes, a 50-year-old Chicago metals trader. But in the pool where he swims these days, he competes against whoever is in the lane beside him, particularly if that athlete appears younger, “and I’m crushed if he’s faster than me, even though he doesn’t know I exist,” says Mr. Rhodes. He still believes, “probably wrongly,” that he could match his long-ago feats in triathlon.

Charles North similarly understands the undying nature of competitive urges. He was relieved when knee troubles ended his record of elite-level distance running, including a 2:46:34 Boston Marathon. As a practicing physician with two young children, “I really didn’t have time to train like that anymore,” he says.

But no sooner did Dr. North start swimming than he began plotting how to finish atop his age group at statewide meets. “Then it occurred to me, ‘What does it matter?’ ” recalls Dr. North, 61. Even so, while cycling in the hills around Albuquerque these days, he often feels compelled to pass the riders he comes upon, he says, especially if they’re younger.

In my case, the aneurysm-induced prohibition against high-intensity aerobics seven years ago presented an ultimatum: Either give up trying my hardest in races, or quit racing altogether. At the time, I was still setting personal records, and training alongside competitors who had the Ironman logo tattooed on their ankles.

Unable to imagine myself aiming for last place, I gave up triathlon. For exercise, I devoted usually an hour a day to walking, riding a stationary bike or jogging around a neighborhood track, and occasionally lifting a few weights.

As the years passed, it began to seem remarkable to me that I had ever engaged in hours-long bouts of exercise. Eventually, I started wondering whether I still had the stamina to do it—even at a snail’s pace, per doctor’s orders.

That’s when the old excitement returned. During Sunday’s triathlon—a one-mile swim, 25-mile bike ride and 6.2-mile run—there were moments when I felt tempted to speed it up, usually to pass somebody. But mostly I resisted, allowing myself to turn it on only in sight of the finish line. After crossing it, I entered the medical tent and checked my heart rate: It was 97. My time was about 2:54. Next year I’m aiming for just over three hours.